In December 2018, Celia Harms sat down in her San Mateo home to write a letter. Over the course of more than 900 words, she told a story that would become familiar to parents from San Diego to Texas to Indiana: Her son had gone to Mexico, visited a pharmacy, bought what he thought were legitimate pills — and died of a fentanyl overdose.

She wanted someone to do something. So she sent the letter to U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, then-Sen. Kamala Harris and then-Rep. Jackie Speier, calling on the three California Democrats to alert the public and sponsor legislation.

“Our beloved son, Jonathan Harms, age 29, was poisoned,” the letter said. “His story is unique in that he didn’t purchase street drugs but went to a brick and mortar pharmacy to buy pain medication for an intractable migraine.”

Since his death in February 2017, that story has become far less unique. A Times investigation earlier this year found that pharmacies in multiple Mexican cities have been passing off powerful illicit drugs as legitimate pharmaceuticals.

The Drug Enforcement Administration and State Department did not warn the public after a Ventura County couple informed them of their own 29-year-old son’s death in 2019 after taking a fentanyl-tainted pill he bought from a Cabo San Lucas pharmacy.

The Times has identified at least half a dozen other American travelers who have overdosed or died since the 2019 incident. Drug experts say it’s likely there are many more casualties.

Jonathan Harms died in 2017 after purchasing fentanyl-tainted pills from a pharmacy in Cancun.

(Harms family)

But the Harms’ story shows the problem began at least two years earlier than was previously known. And it shows federal lawmakers were told about it at least as far back as the end of 2018.

After she sent the letter, Celia Harms followed up several times with each legislator. She has since moved to Rhode Island with Terry Harms, her husband and Harms’ father.

Harris, who is now vice president, never responded, she said. Feinstein’s office sent a letter that noted the senator’s past efforts to fight the raging opioid crisis in the U.S. but “didn’t really address my real issues,” she said. Speier’s office reached out by phone, Celia Harms said, but a staffer there “basically said we can’t do anything because this is a Republican-controlled Congress.”

“We were very adamant that we wanted something to be done,” Terry Harms said. “We sort of got deflated because we felt like it wasn’t really a priority. We just got stock answers to constituent complaints.”

After The Times contacted Feinstein’s office Tuesday, Celia Harms said, one of the senator’s staffers in California called and “apologized that no one offered to meet with” her after she sent the letter in 2018. She added that the staffer said “she’s going to check with the D.C. office” to see what steps can be taken “to make a substantial difference and save lives.”

A spokesperson for Feinstein declined to comment on her office’s communications with Harms in 2018 or to answer a list of questions about why Feinstein did not do more at the time. But the spokesperson confirmed in a one-sentence statement sent via email that Tuesday “Senator Feinstein’s staff reached out to Ms. Harms for a phone conversation” and provided links to information about multiple pieces of federal legislation Feinstein has co-sponsored to address the stateside fentanyl crisis.

Speier and Harris did not respond to requests for comment via email and phone. However, in 2019, Harris exchanged emails with Mary Harrell, the mother of Brennan Harrell, the 29-year-old from Ventura County who died that year.

On Aug. 12, 2019, Mary Harrell sent Harris an email explaining how her son died and asking Harris to “assist us in urging the State Department to provide travel warnings” about counterfeit pills sold by Mexican pharmacies. “Our family is shattered over the loss of our son, and we are hoping his death will at least prevent another family from losing their loved one.”

Eleven days later, Harris sent Mary Harrell an email stating that the State Department had “flagged your case for the U.S. Embassy in Mexico” and encouraging the mother to reach out to the embassy. That October, Mary Harrell sent another email to the then-senator asking her to push for a travel warning.

“Travelers need to be aware of this lack of any control of what is being sold,” Mary Harrell wrote. “My son bought his medication from a pharmacy and dropped dead.”

Nearly a month later, Harris responded in an email Mary Harrell said was the last she received from the then-senator.

“I am forwarding on to you the response I have received from the U.S. Consulate in Tijuana about your concern regarding U.S. Citizens traveling abroad and encountering counterfeit drugs,” Harris wrote. The Times was unable to verify the contents of the response from the consulate that Harris cited.

Terry Harms, left, and Celia Harms at their home in Warwick, R.I.

(Aram Boghosian / For The Times)

Celia Harms did not contact the State Department or the DEA. But she wrote in her 2018 letter to the three lawmakers that “the STATE Department needs to issue warnings to all travelers from the US to Mexico that no drugs are safe to purchase.”

That didn’t happen until last month.

******

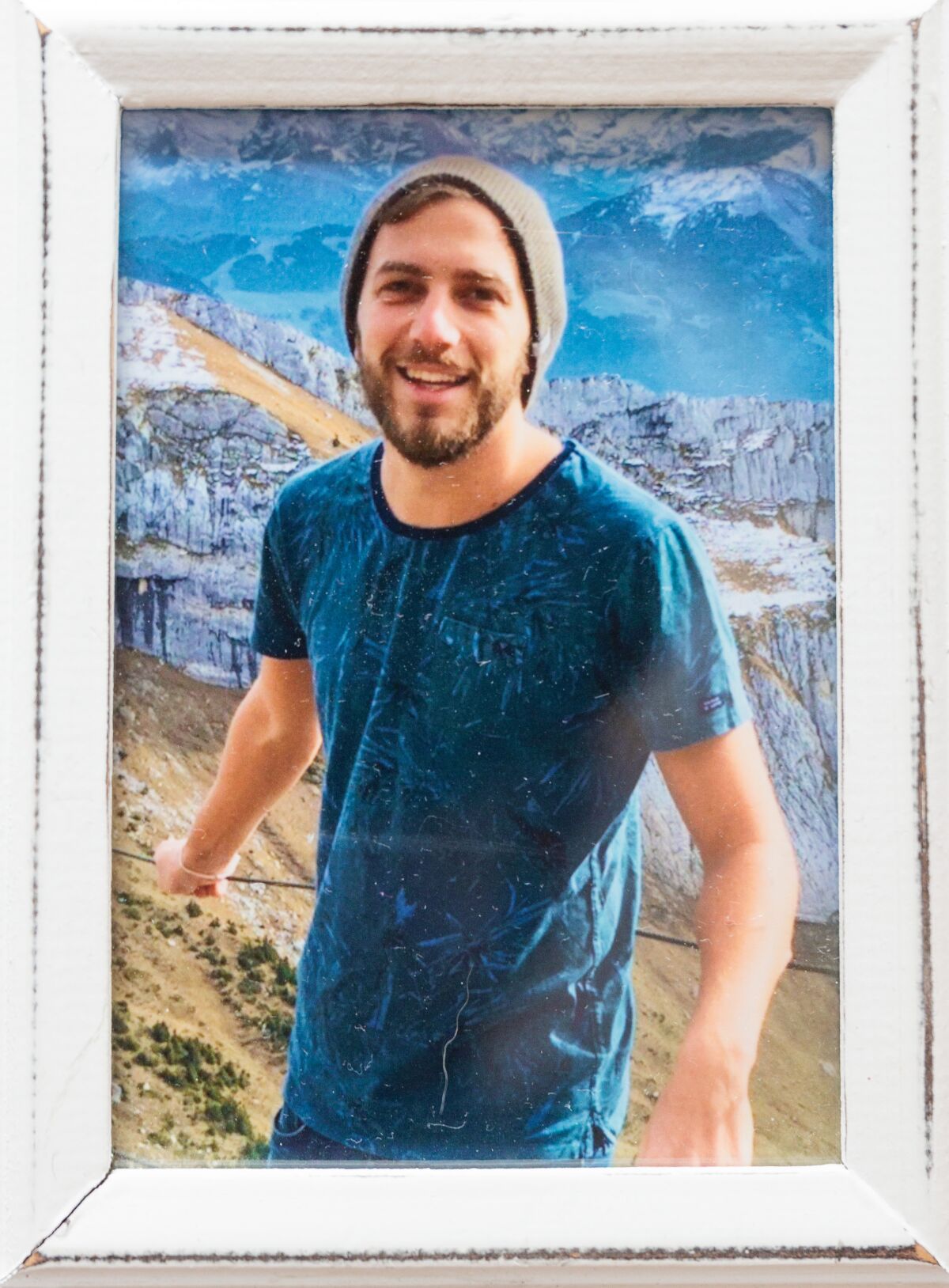

A world traveler who worked in Silicon Valley, Jonathan Harms had lived with severe migraines since he was 6 years old. Growing up, he missed one to three days of school a week because he was in so much pain. By the time he graduated from UC Santa Cruz in 2009, his headaches were still so bad he took prescription pain medication most days and would periodically check into the emergency room.

So when he and his girlfriend, Amanda Tachis, went on a trip to Mexico in early 2017, Harms planned for the worst. He brought along his pain pills and several doses of injectable migraine medication, which he had been prescribed for years. Whenever he sensed a headache was beginning, he would inject Imitrex into his thigh and get some relief.

But while he and Tachis were in Tulum, Harms ran out of the injectable medicine. When he felt another migraine coming on in Cancun two nights before their flight back to the U.S., Harms went looking for the prescription in local drug stores. He couldn’t find it. Instead, he got a bottle of something else. Its label said “Tabletas Migraña” — Spanish for migraine pills — but later laboratory testing showed the pills were actually fentanyl.

A painting of Jonathan Harms with his mother, Celia Harms, painted by his father Terry Harms in 2017, on display at his parents’ home in Warwick, R.I.

(Aram Boghosian / For The Times)

The morning after buying the medication, Harms tried to figure out exactly what it was. He typed “small blue pill 30 M” into Google and clicked a link to a website with a zoomed-in image of a light-blue, circular tablet with “30” imprinted on one side and “M” on the other.

The website identified the pill as oxycodone, but did not mention that the blue “M30” pills are some of the most commonly counterfeited opioids. Since he’d purchased them in a store, he did not know to be wary. So on the morning of Feb. 26, 2017, Tachis says Harms took one of the tablets before heading to the airport.

By the time they boarded their flight back to California, Harms’ condition had begun to deteriorate. Tachis recalls him seeming severely exhausted, uncomfortable and agitated.

“The gate attendant said, ‘Is he OK to fly? Is he on something?’ And I said, ‘No, he gets migraines,’” Tachis said. “Little do we know, he probably had fentanyl in his system.”

*****

When they landed in Los Angeles, Harms was so ill he couldn’t make the connecting flight. Tachis continued on to San Francisco so she could make it back to work the next day. Medics took Harms off the plane and rushed him to the hospital.

A photo of Jonathan Harms taken in 2016, on display at his parents’ home in Warwick, R.I.

(Aram Boghosian / For The Times)

His sister, Eve, lived nearby, so she met him there. He was discharged at about 4:30 p.m. and Eve took him back to her apartment. She and her girlfriend took care of him, but Harms didn’t get any better. At about 8:30 p.m., Eve’s girlfriend found him unresponsive in bed with foam coming out of his nose and mouth and called 911.

“When the paramedics got there, that’s when they found the pills,” Celia Harms said. “They tried to save him but they couldn’t. He was gone.”

The L.A. County coroner’s office determined months later that his cause of death was “fentanyl intoxication” caused by a “drug for migraine headache.” Harms’ parents believe that in addition to the pill he took before his flight, he likely took one or more after he landed in L.A. When police recovered the bottle of counterfeit migraine medication, there were 20 pills inside, of the 24 that the label said it initially contained.

Evan Tenenbaum, one of Harms’ closest friends from childhood through his death, said he believes Harms would still be alive today if the public had known in early 2017 that some Mexican pharmacies were passing off counterfeit pills containing fentanyl as legitimate medications.

“The fact that it’s just beginning to get reported on and get publicity now is insane to me because we knew that this was happening years ago,” Tenenbaum said. “And people have died because we have known this is happening for years now and there have not been any warnings or education about this earlier.”

Celia and Terry Harms at their home in Warwick, RI.

(Aram Boghosian/For The Times)

Nearly two years after her son’s death, Celia Harms finally built up the courage to write to her representatives in Washington.

The two-page letter recalled “the day’s saga and his intense pain.” It recounted the Harms family’s grief over losing a son who was “loving and full of curiosity about life, devoted to making the world a better place.” And it called on the lawmakers who represented the family in Congress to take action, either by passing legislation, pushing federal agencies to act, or raising public awareness.

In the more than four years since she sent the letter, little has been done.

“I thought we would get a much bigger response and that there would be action taken,” Celia Harms said last week. “It was hard for me to imagine that my son died and nobody cared enough to make changes to the laws to prevent other people from dying. But it continues. There’s no change.”